Kenya’s newly elected President, William Ruto has promised that he will lead the country in a new direction, free from the strictures of ethnicity and privileged elitism. Does he have what it takes to lead his people to the Promised Land? Anver Versi and Odhiambo Orlale chart the election that has brought William Ruto to one of Africa’s hottest seats.

The fifth President of Kenya, William Kipchirchir Samoei arap Ruto, took over the instruments of power, following his swearing in on 13 September, after a gruelling, marathon campaign against the veteran politician Raila Odinga, who had thrown his hat in the ring for the fifth time – having failed to be elected to the highest office on each occasion.

Elections in Kenya have never followed the staid and well-trodden path. Each one has thrown up various twists and turns before all parties have settled into the status quo. The 2022 polls were no exception.

The build-up for the polls began relatively slowly as both candidates pushed their manifestos and undertook the now mandatory tour of the country. Expenses were not spared and it soon became clear that this would be the most expensive election in the country’s history.

As the election date on 9 August came closer, both contestants ramped up the temperature with furious mud-flinging that at times seemed to descend to almost infantile, schoolyard levels. Some voters joined in the fray but many kept their powder dry, refusing to declare for either candidate. The ‘ethnicity factor’, so critical in earlier elections, seemed to have lost its potency; policies came under intense scrutiny.

Nevertheless, the voter turn-out of 65%, one of the lowest in the country’s history, reflected a general disenchantment in the political process and declining confidence in the ability of politicians to solve the country’s many problems.

Despite the often bad-tempered campaign speeches, the polling itself was relatively peaceful and many who had barricaded their shops, offices and even houses in case the violence that had marred previous elections, especially in 2007, erupted again, were relieved to see that their caution was not necessary.

In terms of policies, both candidates focused on the economy. Ruto relied on his ‘hustler’ image, making the most of his rags-to-riches story and underlining his bottom-up economic model as he reached out to the youth and women voters, promising them financial support to boost their businesses and plans to create jobs for them.

But the sense of democratic maturity demonstrated by voters during polling itself threatened to unravel once the voting was over and tallying was in progress. Some electoral officials were attacked and fighting broke out. However, thankfully this flare-up of violence was nipped in the bud.

The result was very close, the former Deputy President, William Ruto obtaining 50.49% of the votes to Odinga’s 48.85%. Ruto was declared the winner by Wafula Chebukati, Chairman of the Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC).

Odinga, his running mate – former Constitutional Affairs Minister, Martha Karua – and their supporters objected and filed an election petition challenging the results at the Supreme Court.

The petition, that split the country right down the middle, was heard and determined by seven apex court judges led by Chief Justice Martha Koome, who dismissed it and upheld the election of Ruto, saying that doing otherwise, would be to go against the sovereignty of the people.

According to the Supreme Court, the IEBC had conducted a free, fair and transparent exercise. The court then gave the green light for Ruto to be sworn-in as President a week later, in a public event on 13 September 2022.

Also elected were: Senators (47), Governors (47), County Women Representatives (47), Members of Parliament (337) and Members of the County Assembly (1,450).

Interestingly, perhaps for the first time in Kenya’s independent history, the ‘ethnic factor’ does not seem to have played such an important part in how the voting went as it had on previous occasions. While the majority of the Luo voted for Odinga and the Kalenjin for Ruto, the Kikuyu who held the swing vote – and for once did not have a candidate from their group – voted for whoever they thought would make the best leader.

Who is Ruto?

As his name suggests, Ruto is from the same ethnicity as Kenya’s second President, Daniel arap Moi, who succeeded Jomo Kenyatta in 1978 and ruled, often harshly, until 2002. Arap Moi was nicknamed ‘Professor of Politics’ due to his ability to stay in power by dividing his enemies and making appropriate alliances. However, his reign also ushered in a period known as the ‘lost decade’ when the country’s economy went backwards and the government was accused of cronyism and nepotism.

Ruto is believed to have cut his political teeth when he served as an official of the ‘Youth for Kanu ’92’ organisation, which campaigned for Moi’s re-election in 1992.

Ruto’s much-touted rags-to-riches story, which refers to the time when he sold chickens to support his education at the University of Nairobi, has gone down well with youth struggling to find decent sources of income and given a boost to the millions engaged in informal ‘jua kali’ occupations. His message has been to ‘hustle’ and do whatever it takes to innovate and create occupations for themselves.

He ventured into the murky waters of politics and won the Eldoret North parliamentary seat on his first attempt in 1997 against a powerful ally of President Moi, who was also the Kanu National Chairman.

Ruto has been a long-serving Member of Parliament for Eldoret North in Uasin Gishu County, and was an Assistant Minister and Cabinet Minister in the Moi regime.

He is said to represent the values of his kinsmen in the Rift Valley region, who are world-renowned middle and long distance athletes and who place a high premium on hard work, preparing adequately, studying your opponents, putting on a brave face and always focusing on the bigger prize.

Along the journey, Ruto has faced many challenges locally and internationally and wriggled out of them to soldier on with his dream to be the Head of State. The most serious was being charged with crimes against humanity, when he was accused of orchestrating the post-electoral violence in 2007 that killed more than 1,300 people.

The International Criminal Court abandoned the case for lack of evidence. Eighteen months earlier, the case against Uhuru Kenyatta, accused of the same offences, was similarly dropped. He was also involved in land dispute cases domestically.

Ruto avoided making a political splash as he consolidated his political base and accumulated a substantial fortune from chicken farming, hospitality, oil and gas, plus aviation, making him, reportedly, a shilling billionaire.

Running for high office

He joined Uhuru Kenyatta’s ticket for the 2013 Presidential and general elections against the joint ticket of Raila Odinga and Kalonzo Musyoka. Kenyatta won narrowly, polling 50.5% of the vote. Odinga unsuccessfully contested the result in the Supreme Court.

The same two President / Vice President combinations contested the 2017 election, which Kenyatta won by obtaining 54% of the vote. Once again Odinga challenged the result in the courts and this time the Court ruled the results of the Presidential election null and void, ordering a fresh Presidential election in 60 days.

Odinga withdrew from the second election and Kenyatta, with 98% of the vote following a very poor turn-out, was declared the winner. Odinga refused to accept the result and at one point threatened to stage a rival inauguration with himself as the President. But support for this melted away and Odinga for a while found himself isolated.

Then in March 2018, there was a bombshell when against all expectations, Kenyatta and Odinga staged their famous ‘handshake’, effectively ending decades of hostility. Odinga was given a sinecure. A few months later, as part of the atmosphere of unity, they launched the Bridge Building Initiative (BBI).

This was a massive, nation-wide exercise involving input from a very wide cross-section of the population. The aim was to draft an amended constitution ‘by popular acclaim’, which the initiators said would change the ‘first past the post’ system.

It proposed greatly expanding the National Assembly and the post of Prime Minister would be re-introduced, with the PM appointed and dismissed by the President but also subject to a majority vote of confidence.

William Ruto was one of the fiercest critics of the BBI, putting him at the opposite pole of the new Kenyatta / Odinga alliance. However, the whole BBI structure collapsed when the courts, including the Supreme Court, ruled that it was unconstitutional.

By this time, as Raila Odinga continued to find increasing favour within Uhuru Kenyatta’s circle, Deputy President William Ruto was sidelined and virtually ignored. Ruto put on a brave face and soldiered on, fighting from within the Cabinet and in the 47 counties. As election battle-lines were being drawn, Kenyatta, who was ineligible to stand after his two terms, threw his considerable weight behind Odinga.

It was assumed that many of Kenyatta’s Kikuyu kinsfolk would also support Odinga and that at last, Kenya’s most dogged politician would finally fulfil the destiny that had eluded his father and become the President of Kenya.

Alas for him, it was not to be. His alliance’s Azimio manifesto was heavy on rhetoric but seemed short on concrete policies while Ruto, shrewdly judging the mood of the country, with people worried about rising costs, unemployment, lawlessness and police brutality, provided a set of achievable objectives which he said would transform the lives of the majority while making the country attractive for investment.

He now has the opportunity to put flesh on his pledges. Kenya needs a flexible leader who can bring together the considerable talents in the country, including in enterprise, creativity and above all innovation – the hustler handle – to come to terms with and solve its multitude of economic and social problems. After his time in the political wilderness, will Ruto be the one to lead his people to the Promised Land?

Africa’s top brass embrace Ruto

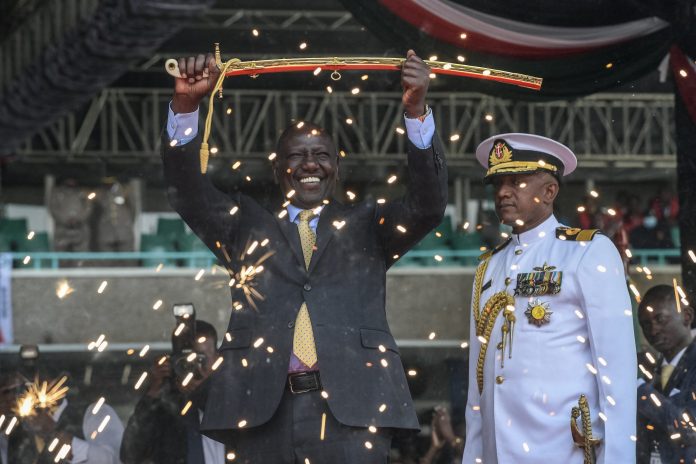

William Kipchirchir Samoei arap Ruto took the Oath of Office on 13 September to become the fifth President of Kenya. A capacity crowd of 60,000, which had filled the Kasarani stadium by dawn, watched as Chief Justice Martha Koome and Judiciary registrar Anne Amadi performed the swearing-in ceremony.

Twenty African Heads of State and very many VIPs from the diplomatic and business worlds attended the vibrant ceremony. The crowd, bolstered by thousands more in the streets who could not gain entry into the stadium, cheered wildly as Ruto raised the Bible and pledged to serve the country to the best of his ability.

He said: “This moment is a moment like no other. It shows that there is a God in heaven; a mere village boy has now become the President of the Republic of Kenya.”

Many in the crowd had travelled long distances across the country, some walking from his homeland hundreds of miles away. There was a mood of optimism with many expressing their belief that Ruto, a self-styled hustler, “is one of us and understands us”. They believed that just as he had pulled himself up by his bootstraps, instead of being the scion of powerful and wealthy dynasties like most of the earlier leaders, he would do the same for them and “make us rich”.

In a gesture of reconciliation and in the interest of unity as Kenya faces one of its most severe economic challenges, Ruto appointed former President Uhuru Kenyatta as the country’s Peace Envoy to the Great Lakes and Horn of Africa region.

He also pledged to support small- scale farmers – the backbone of the country’s economy – by reducing the prices of inputs like fertilizers rather than subsidising food staples and fuel, which he said was an approach prone to abuse.

He committed to returning all shipping clearing functions back to the port city of Mombasa rather than having them at the inland docks in Naivasha. This would provide a much-needed lifeline to clearing and forwarding companies on the coast and boost the flagging economy of the region.

He also said he would increase the annual budgets of the judiciary and national police to make them more independent and more effective in order to combat soaring crime rates and corruption.

Ruto’s 10-point agenda is ambitious but very doable. He will have to find innovative ways of raising the finance needed without resorting to excessive taxation and he will need to appoint a Cabinet based on meritocracy rather than one composed of supporters, allies and loyalists. In Kenya, this is a tall order, but he has said it will not be business as usual. New African wishes the new President and his Cabinet the best of fortune as they work to continue developing one of Africa’s great nations.

— newafricanmagazine